Sometimes there is a Void: Memoirs of an Outsider by Zakes Mda (Book Excerpt)

As I drive back from Bensonvale I wonder how things would have turned out for me, my brothers and my sister if we had not left Sterkspruit. We would have lived here for the rest of our lives, and become teachers and nurses like everyone else, without the exposure to the world that was a result of the single occasion the Boers came for my father in the middle of the night; a whole contingent of white policemen with bright flashlights. They turned the house upside down, looking for ‘terrorist’ documents and banned books. My father’s Communist books were nowhere to be found. I later learnt that he had earlier that week asked our nanny to bury them underground at her place. How did he know he was going to be raided by the police? He must have got a tip from an insider – maybe from a sympathetic black cop.

As I drive back from Bensonvale I wonder how things would have turned out for me, my brothers and my sister if we had not left Sterkspruit. We would have lived here for the rest of our lives, and become teachers and nurses like everyone else, without the exposure to the world that was a result of the single occasion the Boers came for my father in the middle of the night; a whole contingent of white policemen with bright flashlights. They turned the house upside down, looking for ‘terrorist’ documents and banned books. My father’s Communist books were nowhere to be found. I later learnt that he had earlier that week asked our nanny to bury them underground at her place. How did he know he was going to be raided by the police? He must have got a tip from an insider – maybe from a sympathetic black cop.

They took him away in a kwela-kwela police van with bars on the windows. My mother sat at the kitchen table and wept.

The following week was very important for me because I was representing Tapoleng Primary School in a track meet where Herschel District primary schools were competing. I had outrun all competition in middle and long distance races at my school, and it was time to use my famous long strides to bring the trophy to Tapoleng. But how could I do it with my father in jail? It was not so much for him that I felt sorry, but for my mother. I knew he was strong and could handle any situation. After all, we were all terrified of him. I didn’t see how he could fail to terrify the Boers as well. But my mother did not take the arrest well. She worried about how they were treating him in jail and whether they were torturing him or not. Fortunately, she was allowed to take him some food, but never to see him. She cried a lot even as she kept on reminding herself that she needed to be brave for the children.

I lost the race.

The following Monday I went to school as usual, but something unusual happened at the morning assembly. After the prayers the principal Mr Moleko, also known as Mkhulu-Baas, made a speech about the folly of trying to fight against the white man in South Africa.‘There are people who think they can win against the white man,’ he said out of the blue. ‘That is very stupid. Umlungu mdala – the white man is old and wise. What do you think a black person can do to make South Africa a better country? A black person is a baby. If you try to stand up against the white man you will end up in jail.’

I knew immediately that the nincompoop in the threadbare grey suit was talking about my father and I hated him for it.

One evening when we were eating dinner father came home. He was on the run from the police and had come to take a few of his things and to say goodbye.

He went into exile in the British Protectorate of Basutoland, as Lesotho was then known.

We pieced things together later. He was being accused of holding secret meetings all over the Cape, planning the violent overthrow of the state. We had not been aware of all these nocturnal activities because he seemed to be a looming presence at home all the time. A few days after he had been locked up there was a line-up, an identification parade. A certain Mr X was to point out the man who addressed a secret meeting of a PAC cell in a town called Elliot where some acts of sabotage were planned. Mr X was a secret state witness who had attended the meeting, and therefore could not be identified by name. My father knew immediately that the police had already tutored Mr X on how to identify him. He therefore took off his coat and gave it to the man next to him to wear – the people in the line-up were black men picked from the street, and he knew the particular man to whom he gave his coat. He also changed the order of the line-up. Mr X arrived wearing a mask, looked at the men in the line-up and pointed at the man wearing my father’s coat.

‘That’s the man,’ he said. ‘That’s the man who addressed the meeting in Elliot.’

Of course the man would not have held a meeting in Elliot or anywhere else for that matter. The police were angry that their identification parade had been foiled by my father’s cunning. They had to release him, but he knew that was only temporary. It would take them hours rather than days to find other ways of getting him. They would never give up. That was why he didn’t wait for them to rearrest him but escaped to Basutoland.

Once more we were without a father.

The first place to knell his absence was the garden. Old Xhamela had long gone to work for the South African Railways and Harbours and father’s peach trees lost their sculpted shapes. Weeds grew rampant and the seedbeds lay without new seedlings of cabbages, tomatoes and beetroot.

For many days after my father left I could see that my mother’s eyes were red from crying. But soon she got used to the idea of his absence. After all, she had lived alone in Johannesburg for many years while he was either serving articles in the Transkei or was travelling the length and breadth of South Africa, first organising for the ANC Youth League and in later years for the Africanists. She kept herself busy by playing tennis at the township tennis courts whenever she was off-duty from Empilisweni Hospital and sometimes I joined her. Until one day she beat me six-love. I gave up tennis for ever.

I must admit that I enjoyed the freedom that resulted from my father’s exile. For the first time I was able to build a loft and keep pigeons, which my father would never have allowed. Also, my mother was at work for the whole day most days. Or she was doing night-duty, which meant that I could join Cousin Mlungisi in some of his night-time activities. For instance I could go stand outside Keneiloe’s gate and whistle until she came out of the house. Cousin Mlungisi’s girlfriends came out to him when he whistled, and then they would repair behind the outhouse toilet to do naughty things. But my Keneiloe could never come to me. Her parents were too strict. She only stood at the door and waved at me so that I could see she had heard the whistling. Then she walked back into the house before Hopestill got suspicious. That was good enough for me; I had ‘checked’ my girl. I was a fulfilled boy as I walked back home where I had to sneak into my room even though my mother was absent because the nanny was likely to squeal on me if she discovered I had gone to ‘check’ girls.

When Hopestill visited, she and my mother talked about the hardships caused by my father’s absence. They giggled like school girls at something she said to Hopestill. Then Hopestill whispered something back and they burst out laughing. I loved Hopestill at those moments. She was so beautiful. She looked very much like Keneiloe. Then my mother said in a solemn tone, ‘But, Hope, I think it’s a good thing he left when he did. Look at what the Boers have done to Bhut’ Walter and Nel.’ She was talking about her friends Walter Sisulu and Nelson Mandela.

Sometimes there is a Void: Memoirs of an Outsider was written by Zakes Mda, and is an excerpt from his book of the same name.

(Penguin SA, April 2011)

Copyright © Zakes Mda 2011.

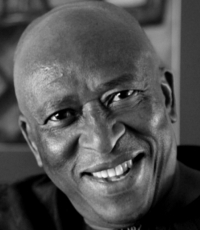

Zakes Mda is an acclaimed South African novelist, poet and playwright. He has won major literary awards for his novels and plays. Sometimes there is a Void: Memoirs of an Outsider is his latest and twenty-fourth book.

Zakes Mda is an acclaimed South African novelist, poet and playwright. He has won major literary awards for his novels and plays. Sometimes there is a Void: Memoirs of an Outsider is his latest and twenty-fourth book.

0 comments:

Post a Comment